Medieval and Renaissance tapestries are among the most impressive and popular works in museums, but because of their massive size, light sensitivity, and fragility, their ongoing preservation requires special attention. Most of MAG’s tapestries came into the collection in the 1920s and 1930s specifically for exhibition in the museum’s great hall, where they were exhibited without interruption for decades. By 2000, only one tapestry was healthy enough to remain on view.

The European Tapestry Initiative began in 2002, when curators at the Memorial Art Gallery determined that the conservation of the museum’s collection of European tapestries was one of its highest priorities. Since that time, four 16th-century Flemish tapestries—Trellised Garden with Animals, Musical Game Park, The Nativity of the Christ Child, and, most recently, The Battle of the Animals —have been conserved at the Textile Conservation Laboratory of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City.

Flemish Renaissance Tapestries

Although tapestries are among the most impressive and popular works in museums today, their size, light sensitivity, and ongoing preservation require special attention.

The majority of European tapestries were made in Germany and France until the early 1500s, when the Flemish towns of Enghien, Oudenaarde, and in particular Brussels, became the dominant tapestry and textile centers. Large, well-organized workshops produced tapestries on a large scale for an international clientele. Wealthy patrons ordered custom-made sets identified with their coats of arms; the less affluent could afford them by ordering existing, less elaborate designs.

Technique

Renaissance tapestries were made of two sets of threads woven on a vertical loom. One, called the “warp,” runs parallel to the length; the other, called the “weft,” runs parallel to the width. The warp threads were stretched tautly on the loom. The weaver then ran the weft threads back and forth through the warp to create a woven design.

Weavers used a full-size drawing, called a “cartoon,” to create the design. It was cut into strips and inserted sideways beneath the warp, where the weaver could see it by opening the threads. Because the weaver was working from the back, the image on the tapestry was the mirror image of the drawing.

The Industry

The Flemish guild system, similar to trade unions, regulated both the production and quality of tapestries. Weavers were required to use the designs of local painters for the images they created on tapestries. Workshop owners employed and trained hundreds of workers, all of whom performed specific tasks.

This highly efficient industry popularized tapestries for the wealthy as well as a large and growing middle class. The main marketing center for Flemish textiles was the city of Antwerp, also known for its furniture and painting production.

The Battle of the Animals

If a single phrase could describe the Renaissance tapestry Battle of the Animals, it would be “frenetic activity, frozen in time.” It’s a lavish, action-packed, and vibrant Renaissance tapestry that was made in Flanders during the 1560s. Purchased in 1926 for the inaugural exhibition of the Gallery’s 1926 addition, it was the first tapestry to enter the museum’s collection. One scholar has described it as “the most remarkable example of a 16th-century animal tapestry in any North American museum.”

Although the tapestry’s city and maker are unknown, the brightly-colored battling animals in the foreground and clusters of human hunters and soldiers in the mid- and background relate it to the Flemish tapestry-making center of Oudenaarde. For its wealthy Renaissance audience, Battle of the Animals served as decoration as well as indoor theater.

The Foreground: The Animals

The foreground of the tapestry teems with exotic animals—both real and fantastic. At the lower left, an ocelot stalks his prey; at the center, the contorted body of a large red hunting dog with a jeweled collar snatches a water fowl from a stream. An ostrich surrounded by different types of reptilian creatures pecks at flora on the stream bank; a unicorn stands nearby.

Scenes of animal combat would have been familiar to the tapestry’s audience, which would have seen them as a form of live entertainment. The educated classes of Renaissance society would have known the more exotic species through illustrations and the real “game parks” of the highest nobility.

The Background: The Hunters

Tapestries like the Battle of the Animals, composed of non-narrative scenes that include forests and lush greenery filled with animals and hunting scenes, are sometimes called “game park” tapestries. Here, hunters and soldiers with their dogs race through the wooded landscape. Some are hunting deer or other wild game; others seem to be pursuing each other. A rabbit, perhaps symbolizing fertility, sits in the crook of the tree at the center mid-ground. A castle and farmstead are seen in the distance.

During the Renaissance, hunting—particularly for boar, stag, and other “noble” game—was a privilege reserved exclusively for the wealthiest, royal classes. Battle of the Animals, with its battling animals in the foreground and hunters in the background, also draws comparisons between the activities of wild animals and humans.

The Border: Hunting and Revelry

Even though usually related by theme, the borders of tapestries were often designed separately from the center portion. Here, the figures in the corners stand with animal mascots. In both the left and right lower corners, Diana, the goddess of the hunt, is shown with her dog. Her presence represents a strong thematic link between the border and the game park activity of the main tapestry.

The remainder of the border is filled with Renaissance ornament, grotesques, satyrs, and animal-headed musicians. It adds additional liveliness to the already action-packed main tapestry, creating an atmosphere of revelry. Many of the ornamental designs probably came from the print sources that were often used by tapestry designers.

Conservation

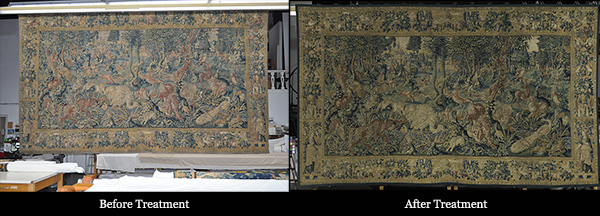

The conservation treatment of Battle of the Animals was a high priority of The European Tapestry Initiative. The tapestry entered the collection in 1926, and was displayed in the galleries of medieval and Renaissance art for several decades before it was taken off view in the 1980s. Almost five centuries of exposure to dirt and light, and the impact of gravity while hanging, had taken a toll. Some of the tapestry’s original brilliant and variegated colors of blue, yellow, green, and reddish-brown had faded to an overall gray, or monochromatic, tone. The upper edges and body suffered most from its many years on display; the weight of hanging literally pulled slits apart, where they could break open with the slightest pressure. In 2011, the museum received a grant to conserve Battle of the Animals from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Over the next 18 months, it was examined, cleaned, and stabilized at the Textile Conservation Laboratory of The Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City.

Conserving MAG’s Tapestries

Cleaning the Tapestry

Rinsing the Tapestry

Stabilizing the Tapestry

Tapestry Linings

Tapestry Hanging Systems

Before & After Conservation

Musical Game Park

With its lively scenes of Renaissance life, Musical Game Park was well suited as a centerpiece for the museum’s long-term installation Renaissance Remix: Art & Imagination in 16th-century Europe (on view 2012-2016). Musical Game Park was conserved in 2008 with the financial support of the National Endowment for the Arts.

Nativity of the Christ Child

The Nativity of the Christ Child, which dates to the early 1500s, is the earliest and smallest of the tapestries conserved under the initiative. It entered the collection in 1979 as a gift from a Gallery patron but required treatment before it could be exhibited. The Nativity was conserved with funding from Dan and Dorothy Gill, the Helen H. Berkeley Conservation Fund, and the Gallery Council of the Memorial Art Gallery.

Trellised Garden with Animals

Trellised Garden with Animals, which was made in the well-known Brussels workshop of Wilhelm de Pannemaker, was acquired in 1931 specifically for exhibition in the museum’s Renaissance gallery. Years of constant display took their toll, and the tapestry was taken down 30 years ago until funds could be raised for treatment. It was conserved at the Textile Conservation Laboratory under a grant from the Instituted of Museum and Library Services in 2009-2010.

Battle of the Animals

Battle of the Animals was the first tapestry to enter MAG’s collection, and the fourth treated under the European Tapestry Initiative under a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Conservation was completed at the Textile Conservation Laboratory in 2013. The exhibition of Battle of the Animals will alternate with that of Trellised Garden with Animals in order to give each a break from exhibition, and preserve both for future generations.

The European Tapestry Initiative has been implemented with financial support from the following organizations and individuals:

- The Institute of Museum and Library Services

- The National Endowment for the Arts

- Dan and Dorothy Gill

- Helen H. Berkeley

- The Gallery Council

Additional thanks go to:

- The Textile Conservation Laboratory of The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York City, Marlene Eidelheit, Director

- Dr. Carmen Niekrasz